National Poetry Month — Paul Doss

April 8, 2022Last year, in honor of National Poetry Month, I asked several past Indiana Poets Laureate their thoughts about the importance of Amanda Gorman’s inauguration poem to the revitalization of American…

Last year, in honor of National Poetry Month, I asked several past Indiana Poets Laureate their thoughts about the importance of Amanda Gorman’s inauguration poem to the revitalization of American poetry and to the health of the nation. This year I decided to pose a larger question to four Hoosiers working outside the field of poetry. I asked:

How do the Humanities help us all cultivate hope and community in times of crisis?

Here is the first response from Dr. Paul K. Doss, president of the Indiana Academy of Science and professor of Geology at the University of Southern Indiana.

Matthew Graham

Indiana Poet Laureate

The environment. It is everything that surrounds an organism.

As an environmental Earth scientist, I look at everything that surrounds us and worry that we are in crisis. Often, I know we are in crisis. The soil, the atmosphere, the oceans, water, forests, glaciers, prairies, biodiversity, our climate and more. All are threatened and most are at risk. And as such, life as we know it is also at risk. It seems many of us don’t recognize this. I have argued solutions to our environmental crises now lie largely in the cultural sphere. Perceptions and beliefs, behaviors and understanding, priorities and vision, hopes and dreams, comfort and fear — these are often what direct societal change.

Science is the endeavor that allows us to describe our natural world and how it works. Science gives us the power and knowledge to understand our environment, recognize problems, and quantify threats. But science doesn’t tell us how to use that knowledge. Our planet’s most pressing environmental problems won’t be solved by science. Preserving biodiversity, protecting water resources, facing the immediate and measurable threats from global climate change, reducing waste generation, and solving the myriad other environmental challenges facing humans can only be achieved by cultural change. And culturally, we are nothing without our our writers, our historians and our philosophers.

It is often the humanities that bring science to the public and bring critical thought and context to the science.

Society reflects a collection of individual behaviors; every one of us is responsible for behavioral change. But do we have the personal, social, cultural and political wherewithal to make those changes before we simply conduct crisis management? All environmental problems are societal problems, meaning their solutions demand teachers, artists, communicators, philosophers, historians, social and political scientists, and natural scientists, engineers and mathematicians. Please don’t think that environmental problems are just for scientists or someone else.

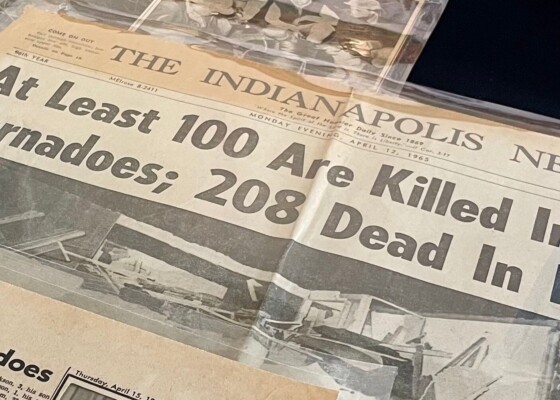

The humanities can make the macro micro, and are better suited to evoke thoughtful connections and responses to crises. That’s a good thing. I want to hear the epidemiologist talking clinically, and I want to hear the historian capture and contextualize the tragedy, the resilience and the joy. The humanities can remind us how to avoid crisis in the first place. And that gives me hope.