What is that? Frankly Fascinating Objects from the Indiana Medical History Museum

October 26, 2017One of my favorite places anywhere is the Indiana Medical History Museum, located on the grounds of the former Central State Hospital, the state’s mental asylum. With its collection of…

One of my favorite places anywhere is the Indiana Medical History Museum, located on the grounds of the former Central State Hospital, the state’s mental asylum. With its collection of brains in jars and turn-of-the-century Victorian gothic atmosphere, it was the perfect setting for Frankenfest, the kick-off event for One State / One Story: Frankenstein.

Given the specific ways the museum helps us understand the history of science and medicine, especially as it relates to theories of the mind and how our personality and consciousness are formed, it was also an appropriate place to think, read and talk about Frankenstein.

The museum is located in what was the pathology building, where doctors researched the physical causes of mental illness. Generations of doctors at the IU School of Medicine also attended dissections and pathology lectures there. When the building closed as an active research facility in the late 1960s, it soon reopened as a museum, keeping intact a remarkable collection of human specimens, patient records, medical instruments and other objects that preserve the history of medicine and psychiatric care in Indiana.

Museum director Sarah Halter selected eight of these objects to highlight during Frankenfest, in a series of curatorial talks. Here’s a bit more about each of the artifacts and how they relate to Frankenstein:

- Brain from patient whose personality changed as a result of a traumatic injury. This object helps us consider some of biggest questions in Frankenstein: Where does personality come from? What makes us who we are? Where does our humanity come from, and can that be lost or taken away? One of my favorite parts of the book is when the Creature describes coming into consciousness. Read it here.

- Anatomical models. How did scientists discover human anatomy? How did new understandings of anatomy affect medicine, science and culture? Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein at a time of renewed interest in human anatomy; doctors and scientists like Victor Frankenstein were eager to get their hands on corpses in order to dissect them (Victor describes his fascination in Chapter 4). Before then, the ideas of Andreas Vesalius were the most significant advancement in anatomical understanding since the writings of Galen, a Greek doctor who lived in the second century. Vesalius’s book De humani corporis fabrica transformed the West’s understanding of human anatomy in the 16th century. These new understandings not only changed science and the practice of medicine, they also contributed to changes in painting and drawing during the Renaissance.

- Admissions papers and painting of the pathology building by Jan Zwara. The papers record the lives and care of two different patients, one (Zwara) from a relatively privileged background who befriended fellow patient Richard Vonnegut and one of a lower socio-economic background. Reading how patients were labeled and described forces us to think about the ways we “other-ize” people who are different than ourselves. The extent to which the Creature’s murderous instincts are caused by social rejection is one of the enduring questions raised by the novel. The scene at the end of Chapter 15 and beginning of Chapter 16, when the Creature is first rejected by the human family he has observed and grown to love, is devastating. All they see is a hideous creature, not like them. The Creature is anguished, and then describes his first violent and anti-social tendencies.

- Pinel Freeing the Insane. Central State Hospital owned a copy of this famous painting, which depicts the moment during the French Revolution when Dr. Pinel unshackled mental patients—the beginning of the Moral Treatment Movement that eventually led to the founding of Central State Hospital in 1848. The movement attempted to imbue more humanistic, along with scientifically-based medical considerations, into the treatment of the mentally ill. Yet, as Frankenstein and the long history of Central State Hospital show, the intentions of scientists and doctors don’t always match the reality. The painting makes us think: What happens when scientists’ ideas and theories don’t go as planned?

- Leucotome. This tool was used for transorbital lobotomies. Lobotomies were the controversial but not uncommon neurosurgical procedure used to treat a variety of mental disorders. Though a lobotomy could alleviate suffering or severe depression, the relief often came at the expense of the patient’s personality and intellect—following the procedure, patients would be less spontaneous, responsive and self-aware. It’s another artifact that asks us to consider very Frankenstein-y questions: What makes us who we are? What are the connections between our physiology and our personality?

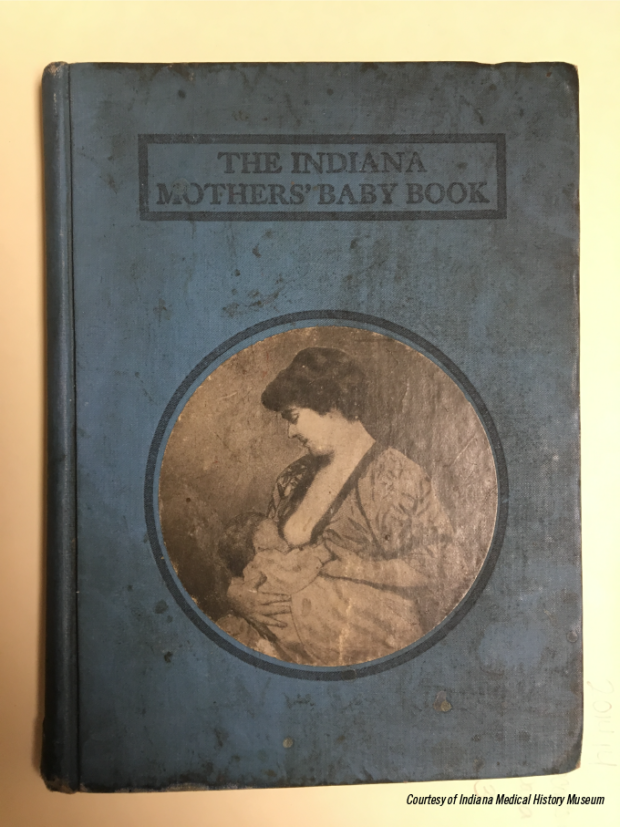

- Better Babies Book. Can we engineer a better human? Should we? What does Frankenstein suggest? This volume was published by the State of Indiana at the height of the eugenics boom in the early 20th century. The “positive eugenics” movement was a public health initiative that encouraged the “right breeding” to weed out inferior characteristics. It was bound up in ideas about racial and ethnic purity, reinforcing stereotypes and labeling non-white Protestant people and features as undesirable, even criminal. Both the eugenics movement and Frankenstein force us to think about what unchecked “science” may lead to, as well as the social conditions that shape the ideas and attitudes of scientists.

- Midwife’s scrapbook. In the 19th century, physicians began to question the value and safety of midwifery; their more scientific methods, doctors claimed, were safer for mothers and babies. Yet some studies showed that midwives were more careful about washing their hands, linens and instruments than physicians, and therefore mothers and babies delivered by midwives had better health outcomes. This is an artifact that lets us consider a key Frankenstein: Does science always know what’s best? What other kinds of knowledge should inform the decisions of doctors and scientists?

- Neuronhurst Sanatorium advertisement. After his tenure leading Central State Hospital, Dr. Fletcher, who had initiated a number of reforms, opened Neuronhust Sanitorium. It may surprise you to learn that this state-of-the-art facility was almost entirely run by women after Dr. Fletcher’s health began to decline. These kinds of hidden histories of women in STEM remind us of Mary Shelley herself, who first published Frankenstein anonymously and who wrote one of the greatest books ever about the practice of science.

Of course, there’s nothing like seeing these objects in person. Next time you’re looking for a Hoosier adventure, head to the Indiana Medical History Museum. Once you’ve been there, I promise you won’t be able to stop thinking and talking about what you’ve learned!

One State / One Story: Frankenstein is made possible by a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this program do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.