Why We Chose All That She Carried

September 7, 2023This year, Indiana Humanities is excited to announce a new selection for our One State / One Story program, All That She Carried by Tiya Miles.

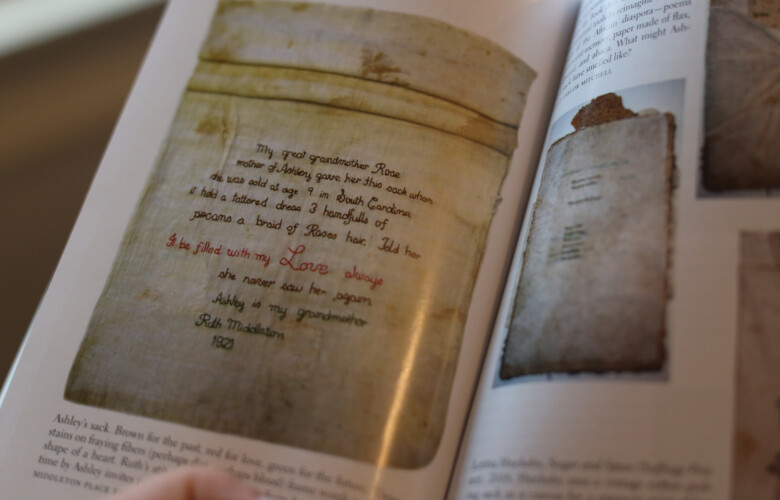

This year, Indiana Humanities is excited to announce a new selection for our One State / One Story program, All That She Carried by Tiya Miles. Winner of the 2021 National Book Award in nonfiction, Miles’ work dives deeply into the history of a single object: a cotton sack embroidered with a few deceptively simple lines.

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

From the sparse information contained in these carefully embroidered lines, Miles opens up the potential worlds of Ashley, Ruth, and Rose. Her analysis of the sack reveals what we can and can’t know about the past, particularly of Black individuals who were brought here by force and enslaved. As Miles writes, “Ruth’s account… stands as a baseline rebuttal to the reams of slaveholder documents that categorized people as objects. Her list of a dress, a braid, pecans and whispered love account for the things that sustained life, rather than rendering lives as things.” The system of slavery operated through the dehumanization of human beings and the breaking of all family ties; the records of who enslaved individuals were, who they were related to and where they were forcibly moved are often lost within this violent and oppressive system, by design. In looking at the sack and its many stories, we learn different, intimate histories of those who experienced slavery, Reconstruction and Jim Crow segregation in our nation.

Though the written records of who Ashley, Ruth and Rose were are not definitive, Miles reveals just how much a single object can tell us about the past. Miles notes, the sack “is at once a container, carrier, textile, art piece and record of past events.” No possible information goes uninvestigated. Moving from the objects in the sack—histories of hair, pecans and dresses—to broader histories such as the architecture of South Carolina, the fabric of the sack cloth, the method of embroidery and the language of the inscription, Miles looks at the sack from all angles. What is revealed is a possible history of these three women and their enduring, resilient love.

If we know ourselves, our communities and our nation through our histories, what does it mean that slavery left glaring omissions in the archives we go to in order to learn about the past? Miles encourages us to look to objects to learn more about our past and how those histories form who we are today. This is a book about an amazing object and the understanding that can be sifted from its construction and contents, but it is also a book about doing history. Miles not only looks to the object itself but also to the way the object has been displayed and interpreted over the years. As she says, interpretations of the past are never final: “While the past itself does not change, the production of history—our studied scrutiny and reconstruction of the past—always shifts over time…I cannot claim to know Rose, Ashley, Ruth or their families intimately. But I take heart from their example of an ethic of bequest, love made manifest in the preservation of things passed on.” Understanding that history is ever evolving and able to teach us important lessons, is key to revealing and interrogating the narratives of our communities and our nation.

At Indiana Humanities, we believe in the power of the humanities to transform individuals, communities and our state. We believe the humanities can connect us through shared histories and experiences. Ashley’s sack, and the historical work that Miles does in All That She Carried, is a prime example of what we think the humanities can do. In learning and contemplating the history of one object, Miles reveals how practicing the humanities helps us imagine more just futures. Rose demonstrated a powerful hope in sending Ashley off with the sack—that she would survive and find a better life. Ashley kept the sack, sharing its story with Ruth in memory of a mother who loved her. Ruth added the inscription, ensuring that those who saw the sack in the future would know this story in all its pain and its hope. They all acted to preserve record of a loving relationship and pass it on to the future. As we take in this history and apply these lessons to our own lives, we begin to think about the things we leave behind, the connections they preserve and what we might pack in our own sacks for future generations to consider and take meaning from.

During One State / One Story, we support communities in coming together to read and talk about this amazing work of historical inquiry. We encourage Hoosiers to think deeply about the legacies of slavery and about the importance of collecting, researching and learning our shared history. We hope participants think about the value of objects in their own lives and how we know ourselves and our ancestors through interacting with the things that are passed on. Finally, we hope that in reflecting on this storied object, Hoosiers are inspired by this remarkable act of love that spans generations, or as Miles says, an act that works to “enhance our ability to peer across other differences—of race and culture, class and status, ability and disability, youth and age.”