Drag Resistance and Worker Solidarity on Indiana Avenue

June 24, 2022Indiana Avenue was the epicenter of Black life for Indianapolis during the jazz era. Emerging research into this local history reveals a queer nightlife and culture moving through and amongst…

Indiana Avenue was the epicenter of Black life for Indianapolis during the jazz era. Emerging research into this local history reveals a queer nightlife and culture moving through and amongst Indiana Avenue and Indianapolis’ Black community with visibility in the jazz clubs and city sidewalks just outside the clubs. Yes, before the Stonewall rebellion in 1969, Indianapolis did have a visible queer presence.

LGBTQ people held public-facing positions along Indiana Avenue and jobs such as female impersonators, now known as drag queens, or male impersonators, now known as drag kings. There was a live-and-let-live ethos during this time of queer identify formation that had a presence that was largely documented in the city’s longest running Black newspaper, the Indianapolis Recorder. These drag performers were working in many jazz venues along Indiana Avenue, including the Madam Walker Theatre. Their support from the community allowed them to thrive to a certain extent.

There isn’t a lot written about what would happen to LGBTQ people if they left Indiana Avenue to visit more White areas around Indianapolis. Yet, the Indianapolis Star did not speak favorably of LGBTQ people during the jazz era. In 1933, Indiana Avenue hosted its very first “pansy ball” at the Paradise Gardens. This show was wildly popular but received a lot of pushback from homophobic people who believed that if gay people were so visible and employed in these jazz clubs, then Black people would never obtain their civil rights. The respectability politics of ever-shifting goal posts didn’t work on other community members who saw a diverse expression of blackness as the only path to progress through solidarity.

A Black woman, Mrs. Holloway, wrote to the Recorder asking why people were offended by the first pansy ball. The Recorder even printed that first pansy ball as an event that put Indianapolis on the map as a world-class city, on par with New York and Chicago.

We don’t often talk about the support and solidarity between workers of varying sexualities who came together and made it possible for LGBTQ people to have employment in a visible and celebratory way. There was some protection provided, and the drag queens who would risk arrest from police raids would sometimes successfully defend themselves openly and fiercely.

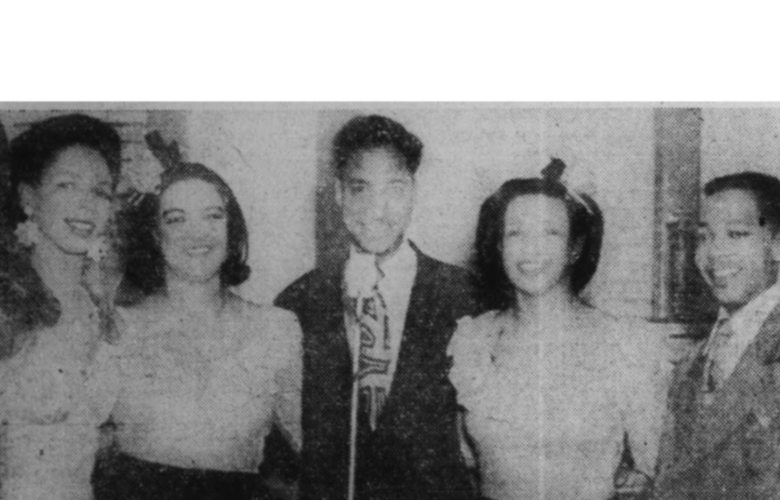

In the 1940s and 50s emerged one of the city’s most well-known drag queens of her time, Doris Duchess White. The Recorder referred to the Duchess as a performer, entertainer and used she/her pronouns. She worked for some time in Chicago with other famous jazz performers like Frankie “Half-Pint” Jaxon, but she found her way back to Indianapolis, where she found great acceptance among the jazz performers and audiences. The Duchess could be seen featured in many ads and pictures advertising jazz shows with drag and other forms of entertainment.

The history of Indiana and Indianapolis is often thought of as conservative, but if you look more closely, you can find threads of progressive and sometimes radical transformations led by working-class people. Just as Indiana can have a D.C. Stephenson, we also have a Eugene Debs. We had a jazz community that supported a wide variety of human expressions. My graduate research at IUPUI into this progressive element of Indianapolis’ history challenges the notion that the Black community is hyper-homophobic, and it seeks to explore LGBTQ visibility pre-Stonewall and how Black LGBTQ people chose to live life outside of the closet and build support, solidarity and community.

Photo credit: Doris (Duchess) White pictured on the left with other performers at the Defense Workers Social Club located at 318 1/2 Indiana Avenue. Published in the Indianapolis Recorder April 29, 1944.